History of the WA Fire Brigade’s firemen and their Union

The Formative Years 1899 -- 1909

The WA Fire Brigade was formed initially by government decree in November 1898. Although the name suggests a statewide coverage this was far from the reality of the day.

At the time there were volunteer fire brigades formed at Perth, Fremantle and throughout a number of the suburbs within the Perth Metropolitan area. The Eastern Goldfields and major country towns such as Albany, Bunbury and Geraldton had also formed volunteer brigades. The newly formed WA Fire Brigades Board (WAFBB) renamed the Perth City Council Fire Brigade as the Metropolitan Fire Brigade. The Metropolitan Fire Brigade maintained a close cooperative relationship with the outer suburban and country brigades.

Despite these statewide ambitions the Metropolitan Fire Brigade was initially responsible solely for the central Perth area. Staffing consisted of Superintendent J P Lapsley, his deputy J Wallis and three firemen. The equipment consisted of two horse carts but no horses. The brigade had use of the Perth City Council Horses, but these were not always available for turnouts as they were not exclusive brigade horses so horses were hired from the cab rank outside the Perth Town hall where the Brigade was first based.

By the end of the first year 11 men were employed and the Brigade owned four horses. Superintendent Lapsley reported to the Board at the end of the first year “they (the horses) are well trained and have become accustomed to their work”.

In this first year the Brigade’s annual budget was £3,113, four ninths paid by the insurance companies, four ninths paid by the Perth City Council and the Colonial Treasury paid the remaining one ninth. The effectiveness of this early force can be measured by the fact a number of country brigades including Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie offered to place their brigades under the auspices of the WAFB. All offers were rejected.

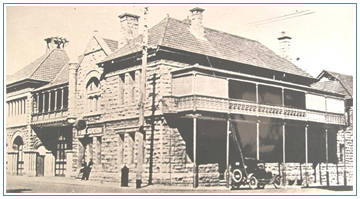

The most urgent problem faced by the WAFBB was where to permanently base the Brigade. Numerous sites were considered before a block on the corner of Murray Street and Irwin Street was purchased for £3,125. Building of the new fire station designed by architect firm Cavanaugh and Cavanaugh, (Lapsley drew sketches for the later additions) began almost immediately.

The new station was commissioned for operations on the 31st December 1900 (first occurrence book entry was midnight January 1st 1901) at a cost of £3,950 and the Brigade immediately moved in. The station complex consisted of an engine-room, a kitchen, stables on the bottom floor, and the Chief Officers office and quarters as well as the men’s quarters forming the first floor. Above them was the attic, which was used at various times as a storeroom or workshop. The Brigade owned the entire Irwin Street frontage and the Irwin Street houses were used as officer’s quarters – a practice which was to lead to considerable friction with the union over the years. The men’s dormitories were used as a gymnasium and lecture room during the day with the first barbell being purchased in 1901. In 1902 with the completion of the hose tower and the paving of the station yard with wooded blocks the station was by and large complete.

In 1904 the Brigade celebrated its first five years in existence. In the first five years the number of staff increased from 12 permanent firemen and 8 auxiliaries to 20 permanent firemen services by a full-time cook. The Brigade also now possessed one steam fire engine, two hose carts, one curricle fire escape, and one exercise wagon, one salvage cart, an ambulance van, 6000 feet of hose, five horses, 71 fire alarms, one smoke jacket and three hand pumps.

The Ambulance had been purchased in 1902 with money raised by public donation and was somewhat egotistically named after the then Superintendent, “The Lapsley Van”. The Fire Brigade Ambulance was great success and during its first five years of operation until 1907 some 822 calls were treated increasing from a yearly rate of 22 in 1902 to 228 in 1907. Lapsley himself was made a honourable member of the Order of St John of Jerusalem for his services in this area and in 1910 he received the Kings Medal – the first Fire Chief in Australia to do so.

In 1905 Fremantle came under the auspices of the Brigade. There was an immediate need for a new fire station with building commencing in 1908 and completed in 1909. Other problems faced included the lack of water mains in North Fremantle and the problem of distances in Fremantle being greater than horses could handle. Both problems were gradually solved.

In 1910 a further step in the expansion of the Fire Brigade occurred when the Fremantle Harbour Trust volunteer Brigade placed itself under the auspices of the Brigade in return for being drilled once per month by the head of the Fremantle Fire Station. This increased the strength of the Brigade by 5 and gave it control of an 850gpm Merriweather fireboat and set the course for future growth of volunteer forces under control of the Brigade.

In little more than ten years the Brigade had grown from four men, no horses, and an annual budget of £3,113 to a staff of 34 permanents, 7 volunteers and a budget of £9,324.

While the Brigade’s record may have been glorious, the life of the men was hard. It was more than a job it was a way of life. The men were initially expected to work 168 hour per week and apply for leave when needed. Only in 1901 were 18 hours leave every ten was reluctantly granted.

The men were expected to start work at 0800 hours and work solid through to 1800 hours or later. The two-hour rest period between 1600 and 1800 hours came in gradually over time.

The men accepted into the Brigade were tradesmen. Sailors especially were recruited into the brigade because of their rope making skills, acceptance of discipline and long shifts as demonstrated by their shipboard past. One consequence of their influence within the Brigade was that the timing and number of times the bells were rung was almost the same as that on a ship.

Perth headquarters resembled a miniature town with stables, carpenters, plumbers and tailors all having their own workshops. The men made the exercise cart, one hose cart, the switchboard, the paintings around the station as well as the painting of the station itself. Uniforms and boots were also made by the men themselves in conjunction with carrying out all the repairs and maintenance of the station.

They lived a rigorous life, often working or training until 10.00 pm as well as drilling for and fighting the occasional fires. On a Monday morning there was steamer drill; on Tuesday morning – hose cart drill; on Wednesday morning – Physical drills; on Thursday morning – Rescue drills; and on Friday after 1902 – Ambulance drill.

Single men were expected to live at the station the whole time and manned the first pump for the night calls. Married men were permitted to live in nearby houses, as long as these houses were connected to the station by house bells. They were still on call and were expected to respond to fire calls when needed, manning the second pump. If they wanted to go out at night, they were expected to visit other firemen also connected to the alarm system and have their bicycles parked outside ready to respond. For this readiness they were paid the grand sum of 10 shillings ($1) per year to maintain their bikes.

The Fireman’s day began at 6 AM when they were woken by the first of the day’s bells. They were expected to breakfast between 7 and 8 ready for the morning parade at 8 o’clock. By this time the station employed a cook and a waiter for the single men. If there was a fire call after 12 midnight the men were permitted to sleep in till 7.30 AM.

For these hours and for this devotion, senior firemen were paid the grand sum of £2/10/- ($5.00) per week. For many of the firemen the conditions were unacceptable. Of the 76 men employed during this period fewer than 21 were left at the end of the first decade. The average length of service of those quitting the Brigade was less than 2.37 years. The overwhelming blame for the staff turnover was that the conditions were simply not good enough, either in terms of hours or pay.

Several attempts were made by the men to gain better conditions, and on the 10th of January 1901 the men threatened to resign en masse. The near mass resignation represented the first industrial action in the history of the WA Fire Brigade.

Nine months later on the 10th October 1901 a dispute arose over hours and leave of absence from the station. After several negotiations the men accepted 12 hours leave of absence from the station every 8 days, with leave being taken from 12 midday to 12 midnight and an average of 157 and a half hour a week. This was not an advancement in terms of hours but was considerable improvement to have the regularity of 12 hours leave of absence every 8 days. These conditions lasted largely unchanged until the 1920’s and staff turnover continued to be high. Clearly something more was required. The formation of a firemen’s union was still a long way off but these events clearly showed firemen needed to have organised representation.

Pre & Post War Years 1909 - 1922

1909 was one of the most revolutionary years in the history of the WA Fire Brigade. At the end of the year the WA Fire Brigade act was passed into law, placing all existing brigades under the control of the WA Fire Brigade.

Funding increased from £9,324 in 1909 to £26,506 in 1910 and by the end of that year the Fire Brigade possessed 18 horses, seven steam engines, seven manual fire engines, one motor tender and one motor turbine engine.

The effect of the WAFB takeover was immediate and striking. By the end of 1911 over fifteen new stations were built. The volunteer services in the Metropolitan area were re-organised with a number being disbanded or displaced by permanent staff.

With the introduction of motorised fire engines the age of horse drawn appliances was coming to an end. One of the principle reasons for the change, apart from the infatuation with engines that was gripping the country at the time, was the limited range of the horse. A mile to a mile and one half seemed to be the full-range of horses charging to fire-calls carting the heavily laden fire engines. This presented particular problems for coverage of fire calls in North Fremantle and up Kings Park hill, which were beyond the range of the horse.

The use of bicycles was common. One fireman, on a bicycle with a bucket, was regularly despatched to put out fires on the Fremantle railway bridge and the North Wharf. Bicycles continued to be used within the Brigade to transport men on fire hydrant checking duty in the Metropolitan area until the Second World War, and in Bunbury until the mid 1950’s.

World War One

The patriotic passion with which WA and indeed Australia met World War One is hard to visualize. The war was seen as a grand adventure, as a courageous duty which only cowards did not want to join. The WA Fire Brigade was no exception and in 1914 the Brigade proudly announced that 25% of its staff had been accepted for front-line duty. By the end of the war some 388 Fire Brigade staff had joined the Empire’s forces – 296 of whom were volunteer firefighters, 52 of whom were permanent and 40 of whom were auxiliaries. The only available casualty figures came from a 1915 report. By then some 10 men had been killed and 20 wounded. This represented 20% of the total number serving. During the war itself some 67% of Australian soldiers were casualties and if this trend was applied to the WAFB some 260 of the men would have been injured in some way or another.

Apart from the horror of the war itself, the war years were steady, though not spectacular for the WAFB. The Brigade continued to have a high turnover of manpower. Between 1914 and 1917 staffing fell from 726 to 536. However by the end of 1918 staffing had recovered. The principle improvement was the arrival of the motorised engines, in 1914 two combination motor turbine pumps and firefighting vehicles arrived and were stationed at Perth and Fremantle. Six motorised hose tenders also arrived and were stationed at Kalgoorlie, Subiaco, North Perth, Maylands, Leederville and Victoria Park.

The arrival of the engines saw the inevitable demise of the horse transport. Horses were sold at Perth in 1914, Kalgoorlie and Fremantle in 1917 and Northam in 1918. The final horse owned by the Brigade was sold to the men of the station at Boulder in 1924.

The arrival of the engines also allowed for a rationalisation of Fire Brigade services throughout the state. One aspect of the reorganisation was the Board’s decision to take full advantage of the services of volunteer firemen wherever practicable. The Board appointed a Superintendent of Volunteer Services, W Richardson, and in two years the volunteers increased from 351 men organised into 24 brigades in 1916 to a peak of 470 men from 29 brigades in 1918. Permanent staffing at Subiaco, Albany and Northam was reduced. While an attempt to form a volunteer brigade at Bunbury failed.

These attempts to expand the volunteers were naturally and rightly seen as a threat to the permanent brigades and is one of the reasons an attempt to form a union was made.

The formation of a union was a complex affair. On one level it was an attempt by firemen to improve the abysmal conditions under which they worked and to counter the general threat posed by the growth of the volunteers. On another level it was part of the general struggle to create an effective union movement in WA. On the general political level it was then part of the Labour Movement’s strategy to detach semi-professional Labor politicians to organise unions in what ever areas they did not yet exist as part of the general struggle against capitalism.

The two men allocated to help form the firemen’s union were George Rice and Albert Green. George Rice who had earlier been involved with the formation of a number of unions helped draft the union’s first constitution. He held no position in the union upon its formation though he was later to hold a number of positions including President and was very influential.

Albert Green also helped on the formation and is one of the most interesting men ever to be involved with the Firemen’s union. Born on the 21st December 1869 at Ballarat he left for the USA at a young age where he became involved in the newly formed Brickmason’s Society in San Francisco. He later left for Guatemala where according to a book of biographies of prominent Western Australians he became a revolutionary in a number of South American countries. After returning to Ballarat he later migrated to Western Australia in 1895.

Green immediately became involved in the Australian Natives Association. This organisation had an influential role in the debate over federation that was then occurring and the vital role the Eastern Goldfield’s vote would have in getting WA to join the Commonwealth. He was also involved in the formation of the local chapter of the Postal Worker’s Union in Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie, which immediately became involved in a long and bitter strike.

In 1900 Green became a member of the Australian Worker’s Union and the Kalgoorlie Social Democratic Party. In 1911 he was elected the local member for Kalgoorlie in State Parliament.

When the Firemen’s Union was formed, Green became the inaugural Secretary. His involvement with the Union ceased shortly afterwards. It is not known to what extent his earlier involvement in the union formation was real or nominal. Nevertheless despite, or perhaps because of the involvement of these political figures, the struggle to create a Fireman’s Union was a difficult one.

The more conservative men in the outstations were suspicious of what they perceived as new and dangerous industrial and political radicalism in their rather insular way of life. It took all the efforts of firemen devoted to the Unionist cause to persuade these men to join. The two key men in this process were Frank Proctor Wilson and Station Officer Peyton. SO Peyton and his wife would tour the outstations by motorbike with sidecar trying to convince the men to join the Union.

On the 11th of September 1916 their labours bore fruit and the Western Australian Fire Brigade’s Employee’s Union was formed and registered before the Industrial Commission with the full agreement of the men.

Frank Wilson became the Union’s first President, while as an officer SO Peyton did not accept any formal position in the union. Six years later he was to resign over what he saw as the Union’s unacceptable politicisation. Other men involved in those early days and probably in the formation of the Union were A B Wright – a fireman who joined the Brigade in 1911 and served as Union Treasurer from 1922 to 1924 – Frank Greiller who also joined the Brigade in 1911 served as President in 1923 – 24. It is not known what influence “the english firemen” coming from their more unionised homeland during the war years had on the formation of the Union.

One of the Union’s first major successes came when fighting the Firemen’s first official wage case before the Commission in 1917. Senior Firemen’s wages went up to the grand some of £3/15/- per week. Hours also decreased, but it is not known by how much.

In terms of fires the war years, with exception of the “Collie fire”, were steady rather than spectacular years. The total number of fires fluctuated between 699 in 1914 to 545 in 1916.

The Collie fire started on the 27th January 1914 and was one of the major fires in the Brigade’s history. Ten buildings in the main street of Collie, including the office of the Collie Miner Newspaper, were destroyed. The fire left the officers and 14 men of the Collie Volunteer Fire Brigade totally exhausted – their manual fire engine having proved totally ineffective against the flames. This fire demonstrated that there was a need for not only improved building construction regulations throughout the State but also for motorised fire engines in country areas.

While the number of fires may have fluctuated erratically, the number of ambulance calls steadily increased with new ambulances being purchased for Perth in December 1914 and Fremantle in 1915.

On a sad note, it must be recorded, that the War years also saw the first death amongst the permanent members of the Fire Brigade. W Studgard of Claremont Station died of a broken neck after having accidentally fallen down the fire pole well.

Post War Years

The final years of the reign of Chief Officer Lapsley saw the Fire Brigade expand after the stagnation of the war years. Ambulances calls continued to increase, 1155 being received in 1920.

In 1921 the WAFB and the St John Ambulance Association officially severed their connections. Why this occurred is not clear but given the complaints implicit in the continual remarks made about the “honoury” nature of the service in the Board’s annual reports, it would appear the dispute was evidently about funding. Whether this was the right thing to do is unknown as both organisations have continued over a long period of time to be very efficient at their individual role.

On an unofficial level co-operation between the two services continued to exist for a number of years. The Perth ambulance hall was situated next to the Brigade headquarters and though the ambulance service possessed two ambulances it only had one driver. Whenever the second ambulance was required a driver from the Fire Brigade was seconded for the trip. It is not known how long this co-operation continued, though it did last throughout most of the 1920s.

During this period staffing increases of the Brigade reflected the Board’s espoused policy of expanding the volunteer forces at the expense of the permanent staff. This bias provoked its inevitable reaction at the beginning of 1922 when the permanent men nearly went of strike over this threat to their livelihood. Firemen at North Perth, Leederville and Geraldton were returned to Perth to make way for volunteers. The strike was only averted and modified to a “go slow” when the auxiliaries in the Metropolitan area went on strike instead. Volunteers at Bunbury and Geraldton also went on strike.

A deputation was sent to the Premier, the ALP State Executive was called on to assist and a report was sent to the WA Newspapers. By the second of February the Board crumbled and the men were reinstated to their original positions.

This represents the first successful industrial action by the Union and the threat of the volunteers was temporarily halted. The problem however remained and continues to do so as the two services – the permanents and the volunteers -- run on totally different lines with totally different philosophies. To quote from the Union President’s address to the ALP State Executive meeting “The only solution to the permanent firemen’s trouble with volunteers is their total extinction.” The dispute has simmered ever since.

The relationship between the permanent firemen and the auxiliaries on the official level was never that good and indeed worsened by the strike even though the auxiliaries had gone out on strike in support of the permanent men. The problem was the auxiliaries wanted backpay for the time they were on strike, and the union had initially pledged to help them. That pledge, however was never fulfilled and despite lengthy efforts the backpay was never gained. The lack of help was never forgotten and similar sympathy action was never again recorded.

Another success of those early years was the gaining of a new award in 1920. Under the terms of the new award pay for a senior firemen was increased to £4/15/- per week. In recognition of the increase cost of living, annual leave was increased to fourteen days per annum and a 103 hour week with 40 hours leave every eight days. This represented a decrease of 54 hours per week from the hours introduced in 1901. Although the eight day cycle for leave away from work remained. The Goldfields allowance was fixed at 5/- per week to compensate for the higher cost of living experienced there. Finally the practice of the married men living off the station while still being on call was continued and the allowance for maintaining their bicycles increased to £1/10/-.

At this time George Rice was President of the Union and Cox serviced as Vice President. It was under there leadership that the era came to an end when in May 1922 James Lapsley recipient of the Kings Medal and member of the Order of St John of Jerusalem, announced his retirement with the firemen. A member and fireman of the Perth Brigade since 1886, the Chief Officer of the Brigade since inception, he was one of the dominant and most important men in the history of the Brigade. On being advised that Lapsley was not “very much provided for his pending retirement”, the Union gave him a “purse with notes” as a retirement present. An era was at an end.

The Twenties

For Western Australia and the WA Fire Brigade the 1920’s were boom times. Expansion followed expansion and no constraints existed upon spending or borrowing. Funding for the Brigade leapt from £34,579 in 1922 to £57,097 in 1929-- an increase of 60%. In real terms the degree in growth was far greater with the Brigade’s debt expanding somewhat erratically from £37,097 in 1924 to £68,663 in 1929.

The money was well spent. New stations were built at Katanning and Merredin in 1920 and North Perth and Leederville in 1926/27. In 1929 in the last pre-depression spending spree, new stations were built at Collie, Northam, Wagin and Victoria Park.

New equipment began to filter through from 1925 onwards. In that year the Brigade installed a 700 gallons per minute (gpm) Dennis at Perth Headquarters. Also four 200 gpm Dennis engines and two smaller Tanami Dennis engines were purchased by the Brigade. In 1928/29 a 600 gpm engine was purchased for Fremantle and four 300gpm were installed at Leederville, Bassendean, Guildford and Merredin.

Many of the vehicles purchased in the 1920’s were to continue in service until late in the 1950’s. These early Dennis engines had solid rubber tires and lacked seating for the firemen who had to stand on the sides or on the back and hang on. Eventually one of them crashed in Hay Street and two firemen fell off the engine. Fortunately no one was killed or seriously injured. No raincoats were provided for firemen at that stage, so firecalls in winter meant the risk of getter soaked and cold.

All the early Dennis engines were all crank started. When the engine backfired or skipped forward, unless the fireman was quick they risked a bruised or broken arm or wrist. One Fireman Bill Collopy, who served as Vice President of the Union from 1925-27, had his arm broken twice by the crank – once when an engine backfired crashing the crank back into his arm and once when it skipped forward. It is not known if his reflexes were simply slower than those of the other men.

One of the biggest advances in firefighting in the 1920’s was the increased availability and use of chemical extinguishes and automatic fire sprinkler systems for shops and factories. By 1929 1,700 chemical extinguishes existed, 39 sprinkler system had been installed and 8 automatic fire alarms were connected to fire stations. Other advancements were in 1923 when all pump fittings were standardised to facilitate the easy use and transfer of equipment and in 1926 for the first time water hydrants were moved onto the road verges in roads under construction.

From the point of view of the Union the decade also had two facets – on one hand conditions and wages improved markedly, while on the other hand in political terms the 1920’s was the most turbulent decade in the Union’s history, with the Union wracked by infighting and by incessant rows with the Labor Party.

One of the greatest gains of the decade was the Union’s final success in its battle with the volunteers and auxiliaries with the number of volunteers declining from the peak of 542 in 1923 to 480 in 1929. This was a consequence of a conscious Board policy not to replace retiring auxiliaries and those remaining were edged towards retirement with no pay rises being granted throughout the decade, despite the increasing cost of living.

The volunteers suffered from the death of Superintendent T Grange in 1921. He was not replaced. Conversely the number of permanent men increased from 77 in 1923 to 124 in 1924. The 1915 decision of the Board to wherever possible depend on volunteers was defeated.

Two issues dominated the first half of the decade – the coming of the 84 hour week and the political fortunes of one man, George Ryce. George Ryce was a professional labor politician who had been involved in the Union since its inception and had helped to draft the Union’s constitution in 1916. By 1920 he was Secretary of the Union and in 1922 was elected President. A socialist with drive and conviction he worked for the West Australian Worker, the labor journal, throughout the early 1920’s and was also instrumental in an attempt to set up a “labor daily” newspaper in WA. His dual role as semi professional politician also allowed him to take time off work whenever required to tour the country areas, something a professional fireman would not have been able to do.

Under his presidency, the Union began 1922 in an extremely radical mood. Money was given to numerous striking unions. Including the Timber Workers Union, the Flour Miller’s Union, the Ironworkers Union and the Printers Union. While £1/1/- was also given to help the starving people of Russia – the only known donation to a foreign country ever made by the Union. Each donation was preceded by a political explanation of the politics and history of that particular strike by George Ryce himself. All members of the executive were addressed as “comrade”. With their recent victory in the dispute where the Union overturned the retrenchment of the 8 permanent firemen that were to be replaced by volunteers, the popularity of George Ryce and the Labor Party, particular the State Executive, who had done so much to help the Union during the dispute, was at an all-tine high.

Perhaps the most radical political move to have been undertaken during the Ryce presidency, was an attempt to affiliate the Union with Australian Workers Union (AWU). An affiliation with the AWU was part of a popular plan of the day to create “One Big Union”. The One Big Union was a radical plan whereby all the workers in their unions would through the process of gradual affiliation band together in one great big federated union and then with a general strike bring capitalism to its knees. With the Russian revolution still being fought and Trotsky’s troops not yet repulsed in Poland, the Revolution for all working people seemed to be just around the corner.

It is in the context of these plans that one of the strongest supporters of the formation of the Union, Station Officer Peyton, resigned because of the perceived politicisation of the Union.

It was one of the most audacious and one of the most ambitious revolutionary plans ever embraced by Australian Labor. Certainly it was the most radical plan ever to be embraced by firemen in Western Australian history. In 1922 they voted 44 for and 30 against the scheme.

Negotiations for federation went ahead. The only problem in any federation or marriage is that to survive together both parties have to remain compatible. In 1923 a more conservative clique gained control of the AWU -- a clique who were totally unacceptable to and antagonistic towards the more radical George Ryce. The plans for federation were quietly dropped and the matter was not mentioned in the minutes again.

Apart from the change in leadership of the AWU, on a more general Australian political level there was a fall in revolutionary fervour throughout the world as the Western countries gradually recovered from the savagery and barbarism of World War One. The idea of the all-powerful General Strike began to lose credence, when the British coal miners strike of 1921 failed because of lack of general union support. The idea collapsed completely when the British General Strike of 1926 also failed. The ultimate weapon had failed to bring Capitalism down.

A second radical plan embarked upon by George Ryce was his attempt to get the Fire Brigade involved in the struggle to create a “Labor Daily” newspaper in Western Australia. The plan was to create a chain of “Labor Dailies” across the country. The reason behind the scheme was recorded to be ….“at the present time the worker receives all his news …through the capitalistic press who seemed to always favour their own requirements and are forever decrying the cause of Labor and its principles.

A general meeting of the Union agreed to strike a levy of 10/- per member to fund the plan. Given that a First Class Fireman’s weekly wage was £4/15/- this represented 11% of their weekly wage or equivalent to $115 per man in today’s terms. Inevitability this move triggered a conservative reaction. Although Kalgoorlie, Boulder, Bunbury, Albany, Fremantle and most of Perth paid their share money was not forthcoming from Geraldton, Northam, East and North Fremantle, Claremont, Subiaco, Leederville, East Perth, North Perth, Victoria Park and Maylands. The Secretary made many visits in an attempt to pressure the men into paying.

Many refused outright arguing amongst other reasons that the levy was too much or against the rules of the Union or “Against all principals of British justice”. Another reason given was that it was really a political levy and most interestingly that “It is an irresponsible levy as to date no one has been appointed from the Labor movement to carry out the spending of the money subscribed.”

The Union Executive believed court cases would be needed to force the payment of the money. The depth and power of the opposition is indicated by the fact that these reasons for refusing to pay were printed in full in the Union Minutes. No one was taken to Court and the Labor Daily never got off the ground. The labour movement today is still decrying the fact that there is only one conservative controlled daily paper in WA that continues to display bias against labour.

As George Ryce was a man involved in journalism and probably would have been central to the publishing of the Labor Daily this scheme was seen by many as an abuse of power. It certainly worked against him for at the end of the year George Ryce lost the Presidency and continued on in the position of Secretary. No more political levies of this nature were made. Thereafter the Union moved to a standard donation of £3 or £5 to the Labor Party election fund each election.

Industrially, a number of interesting and routine issues occurred. In Kalgoorlie in 1923 a dispute broke out with Station-keeper Wrigley – the first of many times that the men working under him were to rebel. Eventually when a strike was threatened in Kalgoorlie itself the Board was forced to act to settle the dispute. Station-keeper Wrigley was transferred to a Metropolitan station.

In 1923 also saw the breaking out of what was to be the most recurrent issue for dispute in Brigade history -- the conflict between merit and seniority as the crucial factor in deciding promotion within the Brigade. The Union demanded that seniority should be the crucial factor in deciding promotion. The Board countered by saying it wanted to consider “efficiency of service as well” meaning they wanted to overlook Senior Firemen in favour of younger better educated individuals into command positions in the Brigade. The issue was never fully resolved.

The first major issue to surface was the idea of a superannuation scheme. The idea was that all firemen with more than five years service contribute a lump sum to start of the scheme, with all firemen making a weekly contribution to it of an unknown amount. A sum of 2/- per week was at one stage suggested but was rejected by the men. The Board was expected to pay into the scheme at a rate of a pound per pound. 55 men voted for a superannuation scheme of which, 50 favoured the specific scheme suggested. The Board opposed the scheme.

Board Chairmen, Dolly Cambell, argued at a meeting of the men, to which he had been invited, that it would be unfinancial because the numbers of men involved would be too small. Also the Government of the day were not willing to contribute one penny towards it. However the Board was willing to collect the money for the scheme and hold it in trust. The matter was held in abeyance until the Board gave a formal response to the scheme. The reply never came and the matter was not raised again until the end of the decade.

The major issue of the post-war era was undoubtedly the planned inception of the two platoon system with a 84 hour week. Before it was introduced the Board offered to borrow £42,000 to build a set of quarters for the men for the firemen in the vicinity of the Perth Station. It was proposed single men would live on the top floor of a two storey building, while married men were to live with their families on the bottom floor. Every apartment would have its own private entrance. Rent would be fixed at a rate of approximately 10/- per week.

The move was supported by Fremantle and Kalgoorlie firemen, who had been having great difficulty in finding reasonable accommodation near the station. However it was opposed at headquarters not only because it was seen as an attempt to forestall the 84 hour week but also because as Mr Hughes MLA argued before the Board:

……….“a fireman’s private life should be away from the place of his daily work. There would not be absolute privacy and indifference between the children would inevitably lead to friction between the women with the possibility of the men becoming involved.” Therefore the harmony of the brigade would be put at risk.

As a counter proposal the Union put forward the idea whereby the Board would build a housing estate for the men, with the money being repaid by the men at the rate fixed by the Worker’s Homes Board. The rate set at the time was 2/6 per £100 spent on the construction of the house – a debt would take at least 16 and one half years to pay off at that rate, with interest not being taken into account of.

The Board did not go ahead with the alternative scheme, nor did it again suggest the idea of quarters, much to the displeasure of the Fremantle and Kalgoorlie firemen.

In 1925 the 84 hour week finally was introduced. The WA Fire Brigade being only the third state to get it behind New South Wales and Victoria. This achievement ranks as one of the greatest in the Union’s History, next to the 56 hour week in 1947 and the 40 hour week in 1970.

Under the new system firemen’s hours were reduced by 14% or 14 hours work per week. The shift began at 8 am and ended at 6 pm, with the night shift working from 6 pm to 8 am. Every third day there was a changeover and one shift had the day off, thus gaining 24 hours in 6 days.

DAY1 DAY2 DAY3 DAY4 DAY5 DAY6

8-6 A A A B B B

6-8 B B A A A B

Firemen thus usually worked 6 days out of every seven day round. If leap years are taken into account, beginning with a shift getting Christmas day off, a fireman would get only 3 Christmas days off in every eight years. They would have to work three Christmas days out of eight and the other two years have to work Christmas night, before the cycle began again. Bar rest days a fireman was always going to or from work at 8 am and 6 pm every day of the year.

Except where necessary for safety reasons drill was forbidden during the night and the period from 4-6 pm was known as “stand-down time” in which no work , except for firecalls was permitted. This system gave a fireman a great deal of leisure time while they were at the station. In the 144 hour cycle, firemen were only working 24 out of 72 hours, except when firecalls occurred in the leisure hours.. This leisure time ensured that the snooker table remained frequently used, while dances continued as a regular event. Pranks, jokes and tales took up a large amount of firemen’s lives.

Engines could be readied for further calls after a firecall. Work on Saturday afternoon Sundays and the public holidays of Eight Hour Day, Christmas Day and Boxing Day were forbidden.

The peculiar hours and irregular rest days – rest days fell on weekends in only 2 out of every eight weeks – meant that firemen still lived apart from the ordinary people. Most of their friends having to be other firemen who shared the peculiar hours and shared the half of the life they spent at the station. It was also hard on a fireman’s wife and family – men complaining that they missed out on their children growing up, spending too little time at home – a fact which seemed very real in the prosperous year’s of the twenties when other work was readily available.

Notwithstanding these issues it was a great improvement over the “continuous service” and the firemen were ecstatic. Possibility the truest reflection of this improvement was the significant fall in resignations. The Fire Brigade was at last beginning to attain the stability it had needed for so long.

In the final aftermath of the 84 hour week, the Board demanded that officers – especially the Chief Officer, Deputy Chief Officer, Third Officer, Motor Engineer, Electrical Engineer and Fremantle District Chief leave the Union. Eventually, they did and on the 24th of June 1925 the Union passed a motion that clearances be issued to all WAFB employees above the rank of Senior Fireman. It was suggested that they form their own industrial organisation. Firemen and Officers were not to be united again under the same organisation until 1980.

In return for letting the Offices leave the Board now agreed to the Union’s demand that all firemen employed by the WAFB must be Union members. The Western Australian Fie Brigade was now a closed shop. Members not paying their dues could be threatened with expulsion from the Brigade. Although the threat was often made, to the extent of available knowledge, punitive measures were never needed to be carried out.

At the same time the men passed a motion ordering the executive to “get in touch with the Eastern States in an attempt to form a Federated Firefighters Union” This attempt to form a United Firefighters Union was to take another 70 years before federal registration could be achieved.

With the introduction of the 84 hour week in March 1925 the firemen were appreciative of the achievement and the efforts of the union executive. A photo of the negotiating committee was “hung in a conspicuous place as a memento of their splendid efforts on the Union’s behalf.” Each member of the committee was given a special token as a memento of the occasion. George Ryce was given £15/15/- in recognition of his “untiring work” in the cause of the Union – equivalent to approximately $4,000 in today’s terms. In comparison the President of the Union received only £5/5/-, to commemorate the occasion.

The balance between the two perhaps reflects the true distribution of power within the Union. George Ryce was the hero of the day. Fame however, especially for heroes and politicians is a fleeting commodity. Less than a year later George Ryce was in disgrace and was to be forced to resign from the Union.